There was some blessing in each case, because I don't have strong regrets about anything being left unsaid. But my brother's death did teach me that you should never go away without telling somebody you love them, because you never know if you're going to see them again.

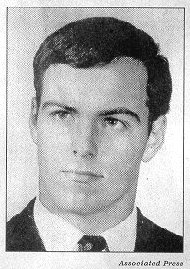

My brother and I were close when we were growing up. We were only sixteen months apart, and consequently, we fought a lot. We played sports together, along with the other kids, but there was a good deal of rivalry between us. Charlie was a natural leader with tremendous charisma; he was elected president of the school we all went to. He was very bright, but he had too much fun politicking to do too much academically.

Many things about Charlie impressed me. I remember him giving his last speech as school president at his graduation dinner. Just before he was due to speak, I saw Charlie sitting at the head table writing away. He was a terrible procrastinator, so I assued he just wasn't prepared. He then stood up and gave an extraordinarily polished speech. I was astonished that an eighteen-year-old kid could do that. To this day, I tend to write my speeches five minutes before I give them, if I write them at all, but they aren't as well organized as his was that evening.

Even at prep school, Charlie exhibited an uncommon maturity. As school president, he had significant influence in disciplinary matters. The faculty had veto power, but he and the headmaster made a lot of decisions about whether someone was going to stay in school or be suspended or expelled. He handled that responsibility extremely well.

He went to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as a political science major. I've been to Chapel Hill many times and taken both my kids to look at it-- it's a great school. As Charlie and I got older, we became very close. I went down to stay with him, and he called me when there were problems in his life he thought I could be helpful with. He hadn't done that before I was at college. I was grateful for the time Charlie and I had after high school. The childhood rivalry was gone, and we became genuine friends as well as brothers.

Charlie did well at UNC and was involved in the student government. I always believed that he would have gone to law school and ended up in politics. After college, Charlie set off on a trip abroad. When you leave college, you're unencumbered and you have a chance to see something of the world. Once you have a job and a wife and children, it's much harder to find the time. I hav always had some guilt because I advised Charlie to travel.

On the first leg of his trip, Charlie sailed to Japan as a passenger on a freighter. He stayed for a few weeks and then took another freighter to Australia. He lived for nine months with a friend on a ranch by the Pascoe River, north of Cairns on the northern tip of Queensland, clearing land. He then went to Indonesia and on to the Southeast Asian country of Laos to visit a friend of our father's who worked for USAID. Together with an Australian friend named Neal Sharman, Charlie stayed in a little bungalow on the Mekong River. He planned to meet up with a friend who was with the Peace Corps in Nepal eventually.

Laos in 1974 was incredibly dangerous; in neighboring Vietnam, Saigon had not yet fallen and the war was raging. U.S. forces bombed the daylights out of Laos because the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which was the supply line from North Vietnam to South Vietnam, went directly through the country. Additionally, Laos was in the middle of its own three-way war between pro-Western, neutralist, and pro-Communist factions. The Communist Pathet Lao guerrilas had been fighting with the Viet Minh in the area since the 1950s; they eventually prevailed and took power in 1975.

This was the situation while Charlie was visiting. He wrote me a letter about what it was like to sit outside his bungalow at night, listening to the thump of distant artillery and the muffled explosions as the shells hit the ground. I almost wrote him back, saying, "What are you thinking? Get out of there-- it's not safe." Then I reminded myself that he was a twenty-three-year-old who was capable of making these judgements himself. I've often wished I had written that letter, although I don't think he would have changed his mind had he read it.

There was speculation that Charlie was in Laos because he was working for the CIA and I think my parents believed that to be the case. Personally, I don't think he was employed by the U.S. government in any capacity, but we'll probably never know the answer to that question.

.

By October 1974, I had moved back in with my parents and was studying for medical school. Charlie had been away from the country for some time; we hadn't heard from him in three months and we were very worried. We'd been writing his friend in Nepal to see if Charlie had shown up. He hadn't.

One day, around ten o'clock in the morning, the phone rang in the apartment. The voice on the other end of the line said, "Is this Mr. Howard Dean?"

I said, "Yes."

It was someone from the State Department. He said, "We have information that shows that Mr. Charles Dean, your son, is a captive of the Pathet Lao." I told him he'd better call my father, which he did. For my parents' sake, I'm glad I was home during the following seven months, but they were some of the most awful months of my life.

We were all shocked that Charlie had been captured, and we began trying everything we could to secure his release. The CIA and the U.S. military provided us with tremendous amounts of information about Charlie, and for that reason, I will always have immense respect for them.

Charlie was classified as a POW-MIA, although we don't know why. It's a good thing he was, because it allowed the U.S. military to do all that they have done for our family over the last twenty-five years. In that time, I've had a window into what it is like to be a family member of somebody who disappeared, died, or was wounded.

In the beginning, we were getting streams of information coming out of Pathet Lao-held territory from people who could freely cross between the zones. We knew were Charlie was, we knew what kind of condition he was in, and we knew what his daily routine was like. We found out that Charlie had indeed been taken by the Pathet Lao. Charlie and Neal had decided to take a raft down the Mekong River to Thailand. On September 5, 1974, they were stopped at a checkpoint near a small village called Pak Him Boun, just two miles southeast of the capital of Laos, Vientiane. The Pathet Lao took the two of them away, apparently because they were carrying cameras. Charlie managed to have a picture of himself smuggled out to the embassy in Vientiane, which alerted us to his plight.

In December 1974, my father went to Laos and tried to meet with Communist officials to persuade them to set Charlie free. He was worried about the meager diet that prisoners were fed and about the risks of diseases like dysentery and malaria. My father left a package of medicine and clothing for Charlie and Neal with Pathet Lao officials, but we've never known if it reached them. In the meantime, we discovered later, Charlie was insisting he be taken to the caves at Sam Neua, in the northern part of the country, where the Pathet Lao had its headquarters. We assume he figured he wasn't able to get anyone locally to make a decision about letting him go.

In February 1975, my mother went to Laos. My father hadn't made much progress on his trip in December, so she was hoping for any news at all. By that time, we had no idea what had happened to Charlie. My mother met one of the Pathet Lao ministers. She said he had looked sideways at her; he wouldn't look her in the eye. She concluded then that Charlie had already been killed. We received notification in May that she was probably right.

Later, we were able to piece together details of what must have happened. Around December 14, 1974, Charlie and Neal were put in a truck and driven away. Witnesses saw the two young men being loaded onto the truck. The next day, the vehicle came back empty, with only the handcuffs that Neal and Charlie had been held with lying in the truck. We assume that Charlie and Neal were executed on or about December 14, 1974.

When I first found out Charlie was probably dead, I was about to take an organic chemistry test. I couldn't think of anything else I could do, so I left the apartment, got on the bus, and went to Columbia to take the exam. I was in a complete daze, and got a 50 on the test. It was a dreadful test that everybody flunked-- and for different reasons than I did-- and the whole class had to retake it.

Charlie's capture and death were the most traumatic events of my life. They have eaten at me ever since. You never get over something like this; all you can do is live with it. It was awful for my two other brothers and me, and it was far worse for our mother and father. It was so painful for my father that he rarely spoke of it afterward. My brothers and I worked for a long time with the Department of Defense and the State Department, looking for information; we shared little of that with my father. He deserved the chance to deal with this in his own way. My mother was more like her sons. She had a way of coping that my father never found.

...

Over the years, the family had kept in touch with the State Department, the CIA, and the Department of Defense about Charlie. We pushed for any scrap of information. Finally, in 2000, there was a break. Through accounts given by people who had seen the two young men killed, the site where Charlie and Neal were believed to have been buried was located.

In February 2002, I decided I would take some time for myself and fly to Vientiane. I wanted to see where Charlie had most likely died.

The countryside there is like no other I have ever seen. The most brilliantly green mountains stick straight up out of the plain. When I came back, I spoke to a group of veterans in Vermont about the place. They became emotional as we talked, and they recalled their service in Vietnam.

I took a helicopter ride down the Mekong River and over the plains and into the mountains along the Laotian border with Vietnam. The Ho Chi Minh Trail was visible, along with evidence of the heavy bombing during the war.

Even today, many of the people of Laos lead a primitive lifestyle, by American standards. The Lao are a very gentle people who have been victimized for generations by a series of bad governments. Laos is presently governed by a Communist dictatorship, but the government was courteous and hospitable to me, and they have been helpful in my brother's case.

When I got to Vientiane, something that had been troubling me for years was resolved. One of the feelings that accompanies survivor's guilt is anger at the person who was killed. You are angry because your loved one left you with this terrible loss. I had never understood why Charlie had gone to Laos and stayed there so long. As I said, I never believed he was working for the U.S. government. When I got to Vientiane, I immediately understood why he'd stayed. When I met the people and felt the pace of the city and learned how gentle and beguiling Southeast Asia was, I appreciated how he had been captivated by it.

I spent time in Laos with members of the Joint Task Force-Full Accounting. The JTF-FA was established in 1992. Young men and women from all four U.S. military branches volunteer to go and live for several weeks in the jungle and look for remains of Americans lost in the war in Southeast Asia.

There was an excavation site set up at the base of a mountain. A plane had been shot down and gone into the side of the hill. It was sobering to think of the enormous power of an airplane going into the side of a mountain or into a streambed at three hundred miles an hour. The Joint Task Force hires entire villages to sift through wreckage, put it in buckets, and bring it to a screening area, where the wreckage is searched for human remains.

I went to five of these sites. We stayed in a base camp at night and traveled out during the day to one of the sites. I was part of the bucket brigade, which brought earth to a central sifting site, and was also part of the screening team.

Life in the camp was great. The task force was just like America, with people of every race and religion. They were wonderful, caring people who had a mission and, furthermore, were very proud of that mission.

We found mostly pieces of equipment-- shards of shattered metal and scraps of uniforms and webbing-- but once in a while, someone would find a tooth or a piece of bone, and a huge cheer would erupt. Any samples would be taken to the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii (CILHI), which operates a DNA-matching lab. Families of POW-MIAs have been asked to provide DNA in case remains are found. My family has had our DNA at the lab for quite some time.

On my last day in Laos, we went to my brother's site. I knew roughly where it was; I had been looking at maps of the area for more than twenty-five years. As we traveled up the road, I saw the villages whose names were so familiar to me.

We were able to meet the farmer on whose land this took place, and we met the witness who had seen my brother's body and the body of his friend lying in the bomb crater where they were buried. In 1974, there had been a construction camp on the site for a North Vietnamese regiment that was building a road. We don't know exactly where Charlie is buried, and in the twenty-five-plus years since he died, what was a construction site has become a rice paddy. The witness couldn't point out the precise location, but he knew there was a large rock nearby, which we found. The crater was supposed to be somewhere in the vicinity, but it had been bulldozed and plowed over.

We got more information from our witnesses. I think they were afraid to speak openly in front of the government representatives who were with us. Still, we were able to get one of the witnesses aside and away from his government minder. There was a U.S. Army interpreter who was a Thai-American and could speak the Lao dialect, so we were able to ask questions out of earshot of the Laotian government.

Some people had claimed that Charlie had been shot while trying to escape. That may be true. Others said he grew sick and died. But I don't believe that two young, healthy twenty-three-year-olds got sick and died on exactly the same day, even if they had been in captivity for three months.

I talked to the eyewitness, whom I'll call Mr. S. Unfortunately, since I'm not a lawyer, I made the mistake of leading the witness. We didn't have much time when we talked with him, so I asked Mr. S. whether the person who killed my brother was North Vietnamese. The place where Charlie had been killed was only about seven miles from North Vietnam, and in order to get to Sam Neua from the southern part of Laos, you'd have to go through North Vietnam. Mr. S. quickly said yes, it was a North Vietnamese. Of course, the witness was only too pleased to oblige me when I served up that option for him. Still, we don't know whether Charlie was killed by the North Vietnamese or someone else. For all I know, it could have been Mr. S. who shot him. He would have been a young soldier at the time. I gave gifts to the farmer and to the witnesses. I know that people involved in the POW-MIA effort from the other side are very worried about being punished for what they said or didn't say, or what they saw or didn't see. I wanted to make clear that our family was very grateful for the information.

A few years ago, what appeared to be a shin bone was recovered from the location where my brother is buried, but the DNA was insufficient to get a match. We don't know if it was part of my brother's body, his friend Neal's body, or even an animal.

This was one of the most emotional days of my life. As we were about to get in the helicopter to leave, I realized that I'd left something behind. I wanted to go back. I just stoood there in front of where the bomb crater might have been, quietly for some time. These were very powerful moments, and for me, it did bring a feeling of closure.

...

I believe this experience sets me apart from many civilians in two ways. First, when I came out against the war in Iraq, I remained very supportive of the troops. I knew what it was like to have somebody close to me disappear and to worry desperately about what had happened. Second, it gave me great respect for the reality of war, though only people who have been in combat can truly understand it. I think the most extraordinary responsibility the president of the United States has is sending American kids to foreign countries to fight and perhaps to die.

I'd like to go back to Laos one more time. I'd like to take my mother and my brothers there. We're still hoping to recover remains, if there are any to be found. The place where Charlie is buried is an incredibly peaceful spot in the mountains, near a tiny creek that was diverted to irrigate a rice paddy.

I often think about the courses our lives might have taken had Charlie been around. One thing is certain: I'm sure that, had he lived, he'd be the one running for president and not me. "

Back to the Dean Dossier

Back to the Dean Dossier Back to General Dean Stuff

Back to General Dean Stuff